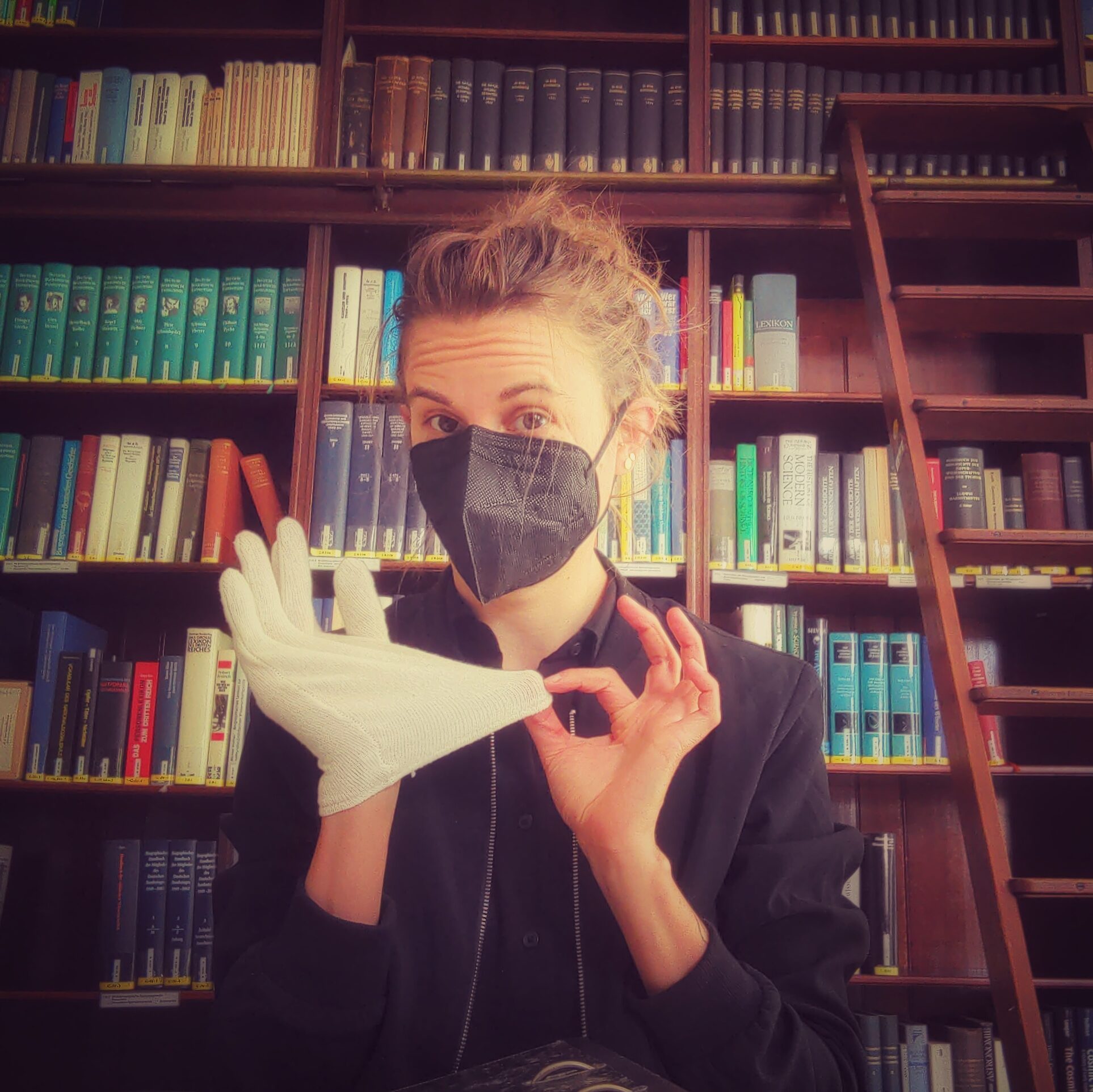

My research takes place in the archive. That’s what I’d like to say. Because I love archives and the atmosphere conveyed by the old documents.

But let’s be honest, the atmosphere of the venerable libraries and archives we know from films and books is rarely encountered these days. The hallowed halls of the Federal Archives in Koblenz–—historians Concerned with Germany know it well—–are rather inhospitable. At least in Koblenz, one can note positively that we are spending less and less time in archives anyway: Because travel budgets and, even more so, time (hinting at the Academic Fixed-Term Contract Act ‚WissZeitVG‘) are scarce, we focus on photographing and digitizing as many sources as possible. only to then painstakingly examine them on our laptops on the train (Deutsche Bahn), categorize them, enter them into various programs, and thus try to extract meaning from them.

Access to contemporary historical sources

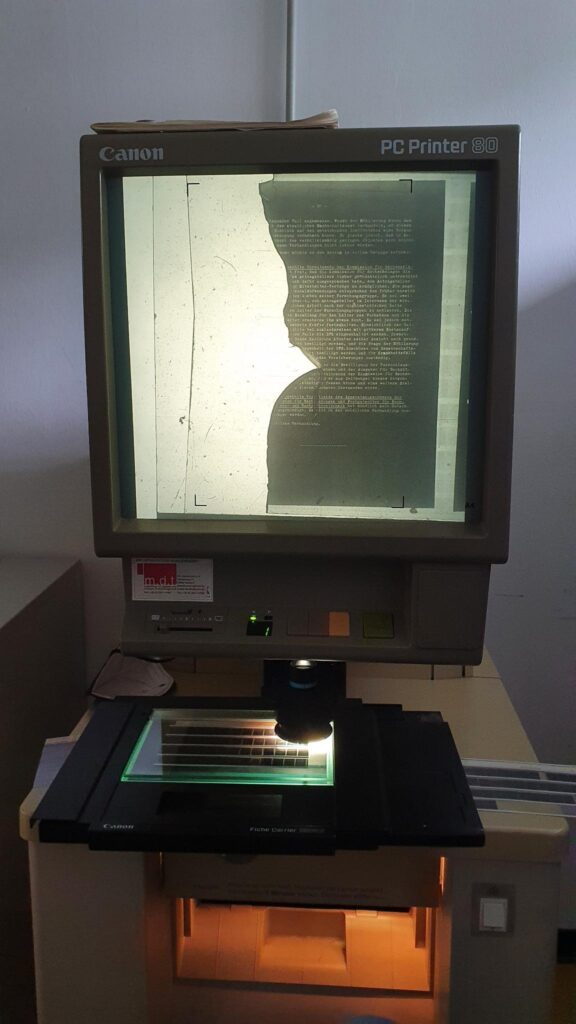

However, Those who work in the field of contemporary history will find that accessing sources is no longer so simple. Besides paper, there are now many different data storage media (in no particular order: photographic film, microfiche, video, floppy disk, slide film, punch cards, CDs, DVDs, etc.), and simply storing them does not mean they can actually be read. Devices capable of reading the various formats must be available, functioning, and maintained. This requires money and expertise.

Sometimes, Alternatively, you can commission scans, prints, copies, or similar services. For just a few items, you usually pay exorbitant sums. Without a well-funded institution, the right grant, or a substantial inheritance, it’s hardly affordable.

Difficulties of digitization

A one-time „digitization“ is not a great solution here. The short history of these attempts has shown that saving data in a format that a computer can read, store, display, and share is not particularly sustainable: On the one hand, the requirements for the quality of the digitization as well as for the formats change – what was high-quality in the past is obsolete from today’s perspective, and what could previously be displayed using (possibly commercial) programs may no longer be possible today.

A look at the USA shows that digitally stored records can, under certain circumstances, be deleted without any difficulty. While a public book or file burning is likely to attract more attention because it has to take place in public, digital archives can disappear almost unnoticed. We have a problem if the originals then no longer exist. Also, there is a problem because computers are meant to process data, too (Yes, indeed!). Images, that is any Data and metadata, can be changed easily. Investigating the provenance of a source, examining its veracity and reliability, is part of a historian’s work. Paper is not forgery-proof. (Konrad Zuse, for example, backdated his documents decades after they were created. We don’t know exactly when the documents were created; we only know when he wanted them to be created.) However, if that awareness isn’t already there, then GenAI should unmistakingly shows us how very sceptical we must be of digitally available datasets too.

Bias in the Archive

Furthermore, by no means everything is being digitized!

Often, historians of (contemporary) science and technology have to hope that A) Teams or single researchers And Engineers have documented their investigations, correspondence, and activities, and B) that these documents were at some point submitted to the university archive or another archive. Scientists and engineers, this is for you! In most German states, according to archive law, documents created in connection with professorial research at universities must be offered to the respective university archive before any destruction or removal.If that’s not enough of an argument, then perhaps the promise to conscientiously place your research in its historical context will convince you? (Or do we need to bring out the big guns and offer a video of a kitten in exchange?)

But Anyway, The archive itself–and this is yet antoher problem–has a historically developed bias. What is preserved is often what decision-makers deem important. In the history of science, this often has been (and still is!) the data of Nobel laureates and successful projects. Due to these priorities, there is hardly any data on so-called ‚invisible hands‘, on women, queer people, racialized or otherwise marginalized individuals who often made this research possible in the first place. Digitization further perpetuates this cycle: here, too, there are certain priorities tied to projects, available funds, and political climates. In some cases, this has led to successes in promoting equality. However, we cannot assume that this will always be the case. A visit to the archive remains essential.

We could enter a cycle where we start again at the top.