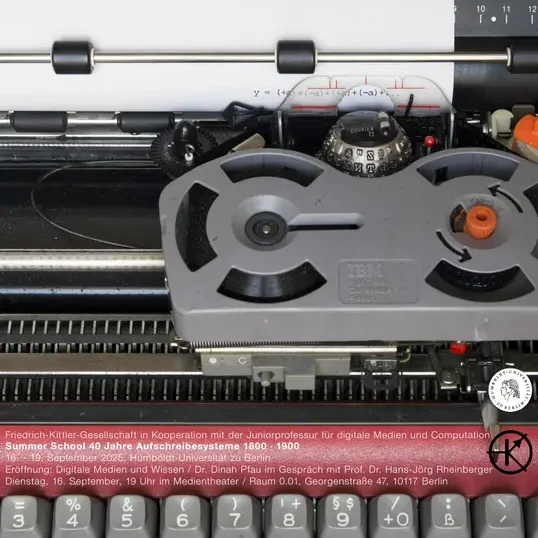

Friedrich Kittler Summer School 2025 „40 Jahre Aufschreibesysteme 1800 · 1900,“ 16.-19. September 2025

2025 was the second year in which the (relatively Young) Friedrich-Kittler-Gesellschaft e. V. in cooperation with the Junior Professorship for Digital Media and Computation at the Department of Media Studies of the Humboldt University of Berlin (Shintaro Miyazaki) organized a summer school. To mark the anniversary of KIttler’s publication, the topic was “40 Jahre Aufschreibesysteme 1800 · 1900“ (engl. Translation: Discourse Networks, 1800/1900).

Even though I did not take part in the whole summer school (there were some archival visits that had to be conducted), together with Hans-Jörg Rheinberger I was invited to a panel discussion on the relationship between Rheinberger’s epistemology and Kittler’s media theory.

Experimentalsysteme

With „Toward a History of Epistemic Things“ (1997), an „Epistemology of the Concrete“ (2006), and the recently published „Split and Splice,“ (to only name a few) Rheinberger has presented studies of modern biology. The experimental system, and within it the practical-epistemic connection between the epistemic thing and the technical object, served him as an access point to his (micro-)studies. The concept of the trace, based on Derrida, plays a crucial role here. Rheinberger understands the experiment, and thus the experimental system, as the core unit of modern sciences, in which the trace acts as a mediator between theory and apparatus, between epistemic thing and technical object. Traces point to something that is, and always will be, beyond the reach of human perception.

In response to my inquiry that night, Rheinberger explained these basic principles of the experimental system and referred to the concepts of analysis and synthesis as they are mirrored in the title of “Split and Splice.” Friedrich Kittler also addressed this topic – albeit from a slightly different perspective. In his later work, Kittler seeks to demonstrate how music and mathematics together represent the beginning of all science. The terms arithmetic and harmony share the same root. Ar (as in ars, ars electronica) describes how logs are joined together to form a raft. Harmony, too, can be understood as a fugue, even the highest form of fugue, because here two tones come together that sound the same but are not identical.

Aufschreibesysteme | Discourse Networks

However, the term that stands out here is another: that of the system. The (at least superficial) similarity between “Experimentalsystem” and “Aufschreibesystem” is striking. This similarity is somewhat lost in the English translation. In short, “Aufschreibesysteme 1800 · 1900” examines two such „discourse networkts“:

First, the one Kittler dates to around 1800. He describes the school reforms implemented in Prussia and elsewhere, and observes that these reforms relied heavily on mothers to teach their children to speak and read using phonics methods. The voice that accompanies silent reading from this point onward is thus linked to the mother’s voice and, at the same time, is mythically elevated in the Romantic era to „Mother Nature.“ The perception of letters and writing recedes into the background during reading; it is the content that we read or „hear.“ The hermeneutic era of Friedrich Schleiermacher has its roots here. Kittler identifies commonalities in various texts from this period, which he places within the context of this discourse network.

The second focus is on the period around 1900, a time when writing lost its monopoly to technical media such as the gramophone and film. They now take over parts of the (linear) storage and transmission. Kittler attributes particular importance to the typewriter, which (like the 1800 writing system before it) is also involved in a shift and specific coding of gender relations. Kittler thus contextualizes sign operations, tropes, and literalness in the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Christian Morgenstern, Sigmund Freud, and Stefan George within the 1900 writing system.

Although Kittler and Rheinberger occasionally refer to each other and both use the term „system“ (which, one might add, has also been subject to certain trends), the differences in their approaches seem to stand out more in the discussion. Rheinberger’s experimental system refers to small, somewhat delimited and manageable units, while Kittler’s concept of discourse networks makes a more global claim. Both, however, clearly incorporate technicity and materiality as conditions of knowledge.

digital information processing and machine learning

I myself have engaged with Rheinberger’s work in light of my research on the history and epistemology of image processing and pattern recognition. It was therefore important to me to also address the question of theories of science and media under the conditions of digital information processing and machine learning.

Rheinberger’s concept of an “Experimental Systems” draws from Gaston Bachelard’s work, especially his concept of phénoménotechnique. Bachelard, and to a slightly different extent Ernst Cassirer and other contemporaries, described a turning point in knowledge around 1900. In his essay „Noumenon and Microphysics,“ Bachelard uses micro- and particle physics as an example of the scientific-experimental generation of phenomena below the microscope’s limit. Peter Galison, in turn, describes the generation of traces in cloud and hydrogen bubble chambers and their translation into a data space. Something, I picked up in my study on the bubble chamber at the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) as well. These are experimental systems par excellence (one might say). However, if we consider recent particle physics, we can see that so-called „events“ are no longer phenomenally traceable. Today, „events“ are generated in a structure of silicon sensors and digital data space. They are still materially grounded, but the traces created are no longer perceptible to the human senses. And the possibilities of machine learning/big data are fueling considerations of a so-called „model-independent“ search for event signatures (see Michael Stöltzner and Peter Maettig). Very similar developments we can see in the life sciences (and Others).

Against the background of these developments, we discussed the question of a new „turn“ in the scientific production of knowledge, as Bachelard and others addressed it in relation to the transition into the 20th century. However, where we stand in this regard today is still difficult to say. A humanities-based examination of contemporary practices of knowledge production within and beyond academia is necessary.

We agreed that this examination must not neglect the material and processual dimensions of research.