DFKI „All-Hands“ Meeting

Visiting other research environments is (almost) always exciting! In November 2025, this environment was the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI). For two days, I participated in the „All-Hands Meeting“ of the DFKI and its cooperation partners – the AI Competence Centres.

Presenting AI history at the DM

The purpose of my visit was to present the Deutsches Museum’s efforts to establish a center for the history of AI and to answer questions from the AI community. For this purpose, I was equipped with a video message recorded by Rudolf Seising (PI of the IGGI project on the history of AI, 2020–23, and of the ArtViWo project, 2024–27), our Director General Michael Decker, and myself.

We had a mere three minutes to introduce the Deutsches Museum, the research institute, and the history of AI in West Germany. A great chance, but rarely enough time to paint a comprehensive picture of what we actually do:

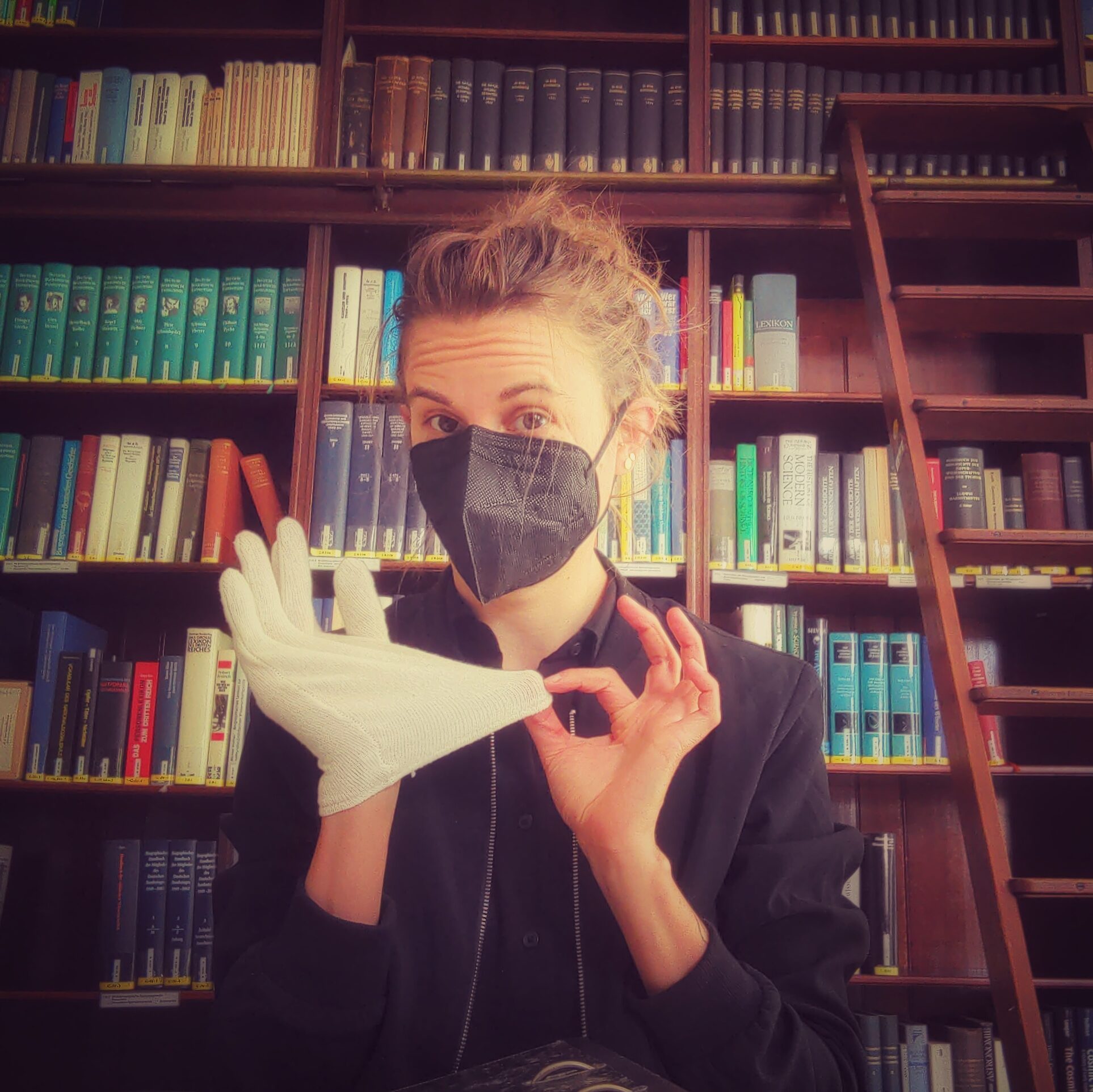

Because An enormous amount of effort goes into ‚doing‘ history! For instance, history can only be written using sources. For many years, we’ve been scouring archives, collecting personal papers and legacies from key figures in AI (research documents, correspondence, photos, etc.), and have already partially transferred these to the DM archive. Not to mention the urgently needed systematic review of all these texts!

We need the scientists‘ Help!

Since archiving is always only sporadic (see here!), we combined the video message with an appeal to the AI researchers to cooperate with us – to give us interviews, entrust us with documents and objects, and open up their networks.

Jörg Siekmann, an old acquaintance and one of the first AI researchers in Germany, supported me on site. with some skill and humor, he was able to ensure that I could address a few words personally to the guests and organizers in addition to the video message. This helped enormously: afterwards, I had many incredibly interesting conversations with people who approached me at the Deutsches Museum out of interest in the history of AI.

Working alone in one’s own room can have its advantages, but it is these moments, when my own passion for the topic is shared by others, that give my work meaning. So Thank you Matthias Temmen and the Other colleagues (also from Lamarr, Bifold and Scads.AI to only name a few) for listening to me going on about the Entanglement of Social, political and ecological Dimensions with „AI“ technologies and Their history!

Foto: Oliver Dietze

So what does it mean (to me) to ‘do’ history of AI? An Unsorted an ad hoc description.

What I’ve noticed in these encounters is that many people aren’t so familiar with what we’re doing in our – perhaps not ivory tower, but due to budget cuts and lack of basic funding – leaning wooden tower of historical humanities.

So here it comes: AI history is a young field. We’ve only just begun. investigations of Most scholars Begin in the first half or middle of the 20th century. But many developments that lead to technologies or practices that we consider part of AI, are older. depending on the perspective (contemporary history, intellectual history, history of knowledge, history of technology, etc.) Their trajectories can even be traced back beyond the 19th century.

In doing so, Many of us attempt to offer a source-based perspective alongside persistent founding narratives (E.G. Dartmouth) and Seasonal myths (E.G. various AI winters); and to contrast a US-centric perspective with a Eurocentric (D’oh!) or Hopefully less Global-North-Centric perspective.

Establishing who was there first

However, For Many practitioners of AI it is important to mention that their Specific country, Here the Federal Republic of Germany, played a significant role in this, both in the long term and in more recent history. That we even were the first ones to invent a certain technology.

This is important with regard to appropriate or just recognition of achievements, to patent issues, legal claims, and the authority to interpret what “AI” actually means. (Depending on the time, place, and „authority,“ AI can mean very different things!).

Although historians often dismiss this question as internalistic, it can be made quite productive in connection with questions about the local production, global transmission, and utilization of knowledge. And as already mentioned: It is also important to counterbalance a history that remains predominantly US-centric.

More than chronology

However, history is much more than chronology and the retelling of theoretical, technical and practical achievements or the names of those involved. And it remains true that primarily the names of the still mostly male researchers are mentioned, while the often female secretaries, technical draftsmen and -women(!) and their achievements remain invisible. Even in 2025.

This is also because the involvement of female (or otherwise marginalized groups) in male fields not always but often took a more enabling role in the background, And they rarely appear by name in the sources and documents. However, some collective and individual achievements of maginalized people have also been rendered invisible for other reasons.

A comprehensive view of historical work considers the contributions of all actors involved, including and especially those whose irrelevance seems obvious to many. Disclaimer: In my opinion, historical disciplines should take a close look precisely where things are taken for granted.

Methodology

Because history done by historians is created from sources that already have intrisic biases, meeting this demand and questioning those things that are taken for granted requires an enormous effort.

This means searching for, finding and eventually collecting, categorizing, analyzing, and evaluating different kinds of sources, using the methods of historical work and research. (Believe it or not, this requires just as much training as…for example, working as a dentist.)

The sources and the results of these processes need to be related to one another and to be placed within the historical – that is, material, social, economic, political, ecological, scientific… – context. A task, that requires comprehensive knowledge of the state-of-the-art literature published by researchers of history and related fields.

-> We need to read a lot.

As a historian of science and technology or a media scholar, I also need to gain an understanding of the subject I am investigating. This means immersing myself in textbooks again, seeking help, and talking to experts. Being taught, making mistakes, learning. How else am I supposed to understand scientific literature or technical circuit diagrams? However, this makes the selection of possible sources all the larger, and can include not only administrative documents, photos and films, but also technical devices or scientific publications.

Theoretical Approach and Research Questions

It is often helpful or even necessary, to approach the extensive material through the lens of theoretical approaches (e.g., from history, philosophy, sociology, …). This makes it possible Or at least easier to establish selection criteria for the types of sources used.

-> We need read a lot but we can never read everything!

Also, theoretical approaches can help us formulate research questions. For example, one could ask why certain technologies emerged, why societies deemed them necessary Or figured it was possible to develop them in the frist Place, why other things were forgotten, and how this can be understood in a local or global context of the time.

We Investigate What the contexts of Use look like, and what role social or political dimensions play with regard to specific technologies or developments. For example: What role do workers‘ rights play in England’s relatively early industrialization? Why was a gendered division of labor important for digitization? In what way has the invention of digital computers contributed to our understanding of „climate“ as a global phenomenon? (Okay, Some of these questions also contain hypotheses, which is important, too)

Let us Disagree

It is quite possible that I may come to different conclusions about developments, reasons and historical trajectories than the people whose research, craft, technologies and practices I am writing about.

Our sources and historical data, for example, indicate that the theory of an AI winter in Germany at the beginning of the 1970s is not necessarily tenable. Similarly, I would not agree in every respect with the definitions (or claims) of what „responsible AI, and diversity in research“ Means, based on what I heard at the DFKI. In a pluralistic society in general, and in science in particular, this should not be a red flag, but simply a good reason for the beginning of a longer conversation.

Understanding | Not judging

And While we all must take responsibility for our actions and should be able to hold others accountable, In my opinion, However, it should Not be the concern of historians to indulge in evaluating The Subject of our investigation in Terms of „Good“ or „Bad“. It is not about praising or condemning, but about understanding developments. This requires caution, prudence, and a great deal of self-criticism.

Keep an open Mind

Never the less, mistakes will happen. Part of research For me is accepting that I cannot know everything and that new sources, new perspectives, other research projects, and researchers can lead to different results. Sometimes we even might have to accept that we agree to disagree.

Being open to different perspectives, sources and discussion is an integral part of the work of a historian (or any researcher!) and can only be achieved if we keep an open mind and don’t stop to educate ourselves.(I’m eyeing the physiology textbook here…)

Uh. what Happened here? What started as a plan to describe the „ALL Hands“ meeting has now turned into more of a mini-statement on the history of AI. Sometimes I guess I just have to reassure myself about my work. And maybe it helps those who, from an outside perspective, wonder what on earth we do all day: We build knowledge networks of a different kind.